The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a

proposed amendment to the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and women in matters of divorce, property,

employment

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any othe ...

, and other matters. The first version of an ERA was written by

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

and

Crystal Eastman

Crystal Catherine Eastman (June 25, 1881 – July 28, 1928)

was an American lawyer, antimilitarist, feminist, socialist, and journalist. She is best remembered as a leader in the fight for women's suffrage, as a co-founder and co-editor with ...

and introduced in Congress in December 1923.

In the early history of the Equal Rights Amendment, middle-class women were largely supportive, while those speaking for the working class were often opposed, pointing out that employed women needed special protections regarding working conditions and employment hours. With the rise of the

women's movement in the United States during the 1960s, the ERA garnered increasing support, and, after being reintroduced by Representative

Martha Griffiths

Martha Wright Griffiths (January 29, 1912 – April 22, 2003) was an American lawyer and judge before being elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1954. Griffiths was the first woman to serve on the House Committee on Ways and M ...

in 1971, it was approved by the

U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

on October 12, 1971, and by the

U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

on March 22, 1972, thus submitting the ERA to the

state legislatures for ratification, as provided by

Article V of the U.S. Constitution.

Congress had originally set a ratification deadline of March 22, 1979, for the state legislatures to consider the ERA. Through 1977, the amendment received 35 of the necessary 38 state

ratifications.

[Article Five of the United States Constitution requires approval of three-fourths of the state legislatures for the enactment of a constitutional amendment. Since 1959, there have been 50 states, so 38 ratifications are required.] With wide, bipartisan support (including that of both major political parties, both houses of Congress, and presidents

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

,

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, and

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

) the ERA seemed destined for ratification until

Phyllis Schlafly

Phyllis Stewart Schlafly (; born Phyllis McAlpin Stewart; August 15, 1924 – September 5, 2016) was an American attorney, conservative activist, author, and anti-feminist spokesperson for the national conservative movement. She held paleocons ...

mobilized

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

women in opposition. These women argued that the ERA would disadvantage housewives, cause women to be

drafted into the military and to lose protections such as alimony, and eliminate the tendency for mothers to obtain custody over their children in divorce cases.

Many

labor feminists also opposed the ERA on the basis that it would eliminate protections for women in

labor law

Labour laws (also known as labor laws or employment laws) are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, ...

, though over time more and more unions and labor feminist leaders turned toward supporting it.

Five state legislatures (Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, Tennessee, and South Dakota) voted to revoke their ERA ratifications. The first four rescinded before the original March 22, 1979 ratification deadline, while the South Dakota legislature did so by voting to

sunset

Sunset, also known as sundown, is the daily disappearance of the Sun below the horizon due to Earth's rotation. As viewed from everywhere on Earth (except the North and South poles), the equinox Sun sets due west at the moment of both the spring ...

its ratification as of that original deadline. It remains an unresolved legal question as to whether a state can revoke its ratification of a federal constitutional amendment.

In 1978, Congress passed (by simple majorities in each house), and President Carter signed, a joint resolution with the intent of extending the ratification deadline to June 30, 1982. Because no additional state legislatures ratified the ERA between March 22, 1979, and June 30, 1982, the validity of that disputed extension was rendered academic. Since 1978, attempts have been made in Congress to extend or remove the deadline.

In the 2010s, due in part to

fourth-wave feminism

Fourth-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began around 2012 and is characterized by a focus on the empowerment of women, the use of internet tools, and intersectionality. The fourth wave seeks greater gender equality by focusing on gende ...

and the

Me Too movement

#MeToo is a social movement against sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and rape culture, in which people publicize their experiences of sexual abuse or sexual harassment. The phrase "Me Too" was initially used in this context on social media in ...

, there was a renewed interest in adoption of the ERA. In 2017, Nevada became the first state to ratify the ERA after the expiration of both deadlines,

and Illinois followed in 2018. In 2020, Virginia's

General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presb ...

passed a ratification resolution for the ERA, claiming to bring the number of ratifications to 38. However, experts and advocates have acknowledged legal uncertainty about the consequences of the Virginian ratification, due to expired deadlines and five states' revocations.

Resolution text

The resolution, "Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States relative to equal rights for men and women", reads, in part:

Background

On September 25, 1921, the

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

announced its plans to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to guarantee women equal rights with men. The text of the proposed amendment read:

Alice Paul, the head of the National Women's Party, believed that the

Nineteenth Amendment would not be enough to ensure that men and women were treated equally regardless of sex. In 1923, at

Seneca Falls, New York

Seneca Falls is a town in Seneca County, New York, United States. The population was 8,942 at the 2020 census.

The Town of Seneca Falls contains the former village also called Seneca Falls. The town is east of Geneva, New York, in the nor ...

, she revised the proposed amendment to read:

Paul named this version the

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

Amendment, after a female abolitionist who fought for women's rights and attended the First Women's Rights Convention. The proposal was seconded by Dr.

Frances Dickinson, a cousin of

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

.

In 1943, Alice Paul further revised the amendment to reflect the wording of the

Fifteenth

In music, a fifteenth or double octave, abbreviated ''15ma'', is the interval between one musical note and another with one-quarter the wavelength or quadruple the frequency. It has also been referred to as the bisdiapason. The fourth harmonic, ...

and Nineteenth Amendments. This text became Section 1 of the version passed by Congress in 1972.

As a result, in the 1940s, ERA opponents proposed an alternative, which provided that "no distinctions on the basis of sex shall be made except such as are reasonably justified by differences in physical structure, biological differences, or social function." It was quickly rejected by both pro and anti-ERA coalitions.

Feminists split

Since the 1920s, the Equal Rights Amendment has been accompanied by discussion among

feminists

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

about the meaning of women's equality.

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

and her

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

asserted that women should be on equal terms with men in all regards, even if that means sacrificing benefits given to women through protective legislation, such as shorter work hours and no night work or heavy lifting. Opponents of the amendment, such as the

Women's Joint Congressional Committee, believed that the loss of these benefits to women would not be worth the supposed gain to them in equality. In 1924, ''The Forum'' hosted a debate between

Doris Stevens

Doris Stevens (born Dora Caroline Stevens, October 26, 1888 – March 22, 1963) was an American suffragist, woman's legal rights advocate and author. She was the first female member of the American Institute of International Law and first cha ...

and

Alice Hamilton

Alice Hamilton (February 27, 1869Corn, JHamilton, Alice''American National Biography'' – September 22, 1970) was an American physician, research scientist, and author. She was a leading expert in the field of occupational health and a pioneer ...

concerning the two perspectives on the proposed amendment. Their debate reflected the wider tension in the developing feminist movement of the early 20th century between two approaches toward gender equality. One approach emphasized the common humanity of women and men, while the other stressed women's unique experiences and how they were different from men, seeking recognition for specific needs. The opposition to the ERA was led by

Mary Anderson and the

Women's Bureau

The United States Women's Bureau (WB) is an agency of the United States government within the United States Department of Labor. The Women's Bureau works to create parity for women in the labor force by conducting research and policy analysis, to ...

beginning in 1923. These feminists argued that legislation including mandated minimum wages, safety regulations, restricted daily and weekly hours, lunch breaks, and maternity provisions would be more beneficial to the majority of women who were forced to work out of economic necessity, not personal fulfillment. The debate also drew from struggles between working class and professional women. Alice Hamilton, in her speech "Protection for Women Workers", said that the ERA would strip working women of the small protections they had achieved, leaving them powerless to further improve their condition in the future, or to attain necessary protections in the present.

The

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

already had tested its approach in

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, where it won passage of the Wisconsin Equal Rights Law in 1921. The party then took the ERA to Congress, where U.S. senator

Charles Curtis

Charles Curtis (January 25, 1860 – February 8, 1936) was an American attorney and Republican politician from Kansas who served as the 31st vice president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 under Herbert Hoover. He had served as the Sena ...

, a future

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, introduced it for the first time in October 1921.

Although the ERA was introduced in every congressional session between 1921 and 1972, it almost never reached the floor of either the Senate or the House for a vote. Instead, it was usually blocked in committee; except in 1946, when it was defeated in the Senate by a vote of 38 to 35—not receiving the required two-thirds supermajority.

Hayden rider and protective labor legislation

In 1950 and 1953, the ERA was passed by the Senate with a provision known as "the Hayden rider", introduced by

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

senator

Carl Hayden

Carl Trumbull Hayden (October 2, 1877 – January 25, 1972) was an American politician. Representing Arizona in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1969, he was the first U.S. Senator to serve seven terms. Serving as the state's first Represe ...

. The Hayden rider added a sentence to the ERA to keep special protections for women: "The provisions of this article shall not be construed to impair any rights, benefits, or exemptions now or hereafter conferred by law upon persons of the female sex." By allowing women to keep their existing and future special protections, it was expected that the ERA would be more appealing to its opponents. Though opponents were marginally more in favor of the ERA with the Hayden rider, supporters of the original ERA believed it negated the amendment's original purpose—causing the amendment not to be passed in the House.

ERA supporters were hopeful that the second term of President

Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

would advance their agenda. Eisenhower had publicly promised to "assure women everywhere in our land equality of rights," and in 1958, Eisenhower asked a

joint session of Congress

A joint session of the United States Congress is a gathering of members of the two chambers of the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Joint sessions can be held on ...

to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, the first president to show such a level of support for the amendment. However, the National Woman's Party found the amendment to be unacceptable and asked it to be withdrawn whenever the Hayden rider was added to the ERA.

The

Republican Party included support of the ERA in its platform beginning in

1940, renewing the plank every four years until

1980.

The ERA was strongly opposed by the

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

and other labor unions, which feared the amendment would invalidate protective labor legislation for women.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

and most

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

ers also opposed the ERA. They felt that ERA was designed for middle-class women, but that working-class women needed government protection. They also feared that the ERA would undercut the male-dominated labor unions that were a core component of the

New Deal coalition. Most Northern

Democrats, who aligned themselves with the anti-ERA labor unions, opposed the amendment.

The ERA was supported by Southern Democrats and almost all Republicans.

At the

1944 Democratic National Convention, the Democrats made the divisive step of including the ERA in their platform, but the Democratic Party did not become united in favor of the amendment until congressional passage in 1972.

The main support base for the ERA until the late 1960s was among middle class Republican women. The

League of Women Voters, formerly the

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

, opposed the Equal Rights Amendment until 1972, fearing the loss of protective labor legislation.

1960s

At the

Democratic National Convention in 1960, a proposal to endorse the ERA was rejected after it was opposed by groups including the

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

(ACLU), the

AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 12 million ac ...

, labor unions such as the

American Federation of Teachers

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) is the second largest teacher's labor union in America (the largest being the National Education Association). The union was founded in Chicago. John Dewey and Margaret Haley were founders.

About 60 per ...

,

Americans for Democratic Action

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) is a liberal American political organization advocating progressive policies. ADA views itself as supporting social and economic justice through lobbying, grassroots organizing, research, and supporting pro ...

(ADA), the

American Nurses Association

The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a 501(c)(6) professional organization to advance and protect the profession of nursing. It started in 1896 as the Nurses Associated Alumnae and was renamed the American Nurses Association in 1911. It is b ...

, the Women's Division of the

Methodist Church, and the National Councils of Jewish, Catholic, and Negro Women. Presidential candidate

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

announced his support of the ERA in an October 21, 1960, letter to the chairman of the National Woman's Party. When Kennedy was elected, he made

Esther Peterson the highest-ranking woman in his administration as an assistant secretary of labor. Peterson publicly opposed the Equal Rights Amendment based on her belief that it would weaken protective labor legislation.

Peterson referred to the National Woman's Party members, most of them veteran suffragists and preferred the "specific bills for specific ills" approach to equal rights.

Ultimately, Kennedy's ties to labor unions meant that he and his administration did not support the ERA.

President Kennedy appointed a

blue-ribbon commission on women, the

President's Commission on the Status of Women

The President's Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) was established to advise the President of the United States on issues concerning the status of women. It was created by John F. Kennedy's signed December 14, 1961. In 1975 it became the ...

, to investigate the problem of sex discrimination in the United States. The commission was chaired by

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, who opposed the ERA but no longer spoke against it publicly. In the early 1960s, Eleanor Roosevelt announced that, due to unionization, she believed the ERA was no longer a threat to women as it once may have been and told supporters that, as far as she was concerned, they could have the amendment if they wanted it. However, she never went so far as to endorse the ERA. The commission that she chaired reported (after her death) that no ERA was needed, believing that the Supreme Court could give sex the same "suspect" test as race and national origin, through interpretation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution. The Supreme Court did not provide the "suspect" class test for sex, however, resulting in a continuing lack of equal rights. The commission did, though, help win passage of the

Equal Pay Act of 1963

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 is a United States labor law amending the Fair Labor Standards Act, aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex (see gender pay gap). It was signed into law on June 10, 1963, by John F. Kennedy as part of his New Fro ...

, which banned sex discrimination in wages in a number of professions (it would later be amended in the early 1970s to include the professions that it initially excluded) and secured an

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

from Kennedy eliminating sex discrimination in the

civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

. The commission, composed largely of anti-ERA feminists with ties to labor, proposed remedies to the widespread sex discrimination it unearthed.

The national commission spurred the establishment of state and local commissions on the status of women and arranged for follow-up conferences in the years to come. The following year, the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

banned workplace discrimination not only on the basis of race, religion, and national origin, but also on the basis of sex, thanks to the lobbying of

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

and

Coretta Scott King

Coretta Scott King ( Scott; April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader who was married to Martin Luther King Jr. from 1953 until his death. As an advocate for African-American equality, she w ...

and the political influence of Representative

Martha Griffiths

Martha Wright Griffiths (January 29, 1912 – April 22, 2003) was an American lawyer and judge before being elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1954. Griffiths was the first woman to serve on the House Committee on Ways and M ...

of

Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

.

A new women's movement gained ground in the later 1960s as a result of a variety of factors:

Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan ( February 4, 1921 – February 4, 2006) was an American feminist writer and activist. A leading figure in the women's movement in the United States, her 1963 book ''The Feminine Mystique'' is often credited with sparking the se ...

's bestseller ''

The Feminine Mystique

''The Feminine Mystique'' is a book by Betty Friedan, widely credited with sparking second-wave feminism in the United States. First published by W. W. Norton on February 19, 1963, ''The Feminine Mystique'' became a bestseller, initially selling o ...

''; the network of women's rights commissions formed by Kennedy's national commission; the frustration over women's social and economic status; and anger over the lack of government and

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

enforcement of the Equal Pay Act and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. In June 1966, at the Third National Conference on the Status of Women in

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, Betty Friedan and a group of activists frustrated with the lack of government action in enforcing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act formed the

National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

(NOW) to act as an "NAACP for women", demanding full equality for American women and men.

In 1967, at the urging of Alice Paul, NOW endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment. The decision caused some union Democrats and social conservatives to leave the organization and form the

Women's Equity Action League The Women's Equity Action League, or WEAL, was a United States women's rights organization founded in 1968 with the purpose of addressing discrimination against women in employment and education opportunities. Made up of conservative women, they use ...

(within a few years WEAL also endorsed the ERA), but the move to support the amendment benefited NOW, bolstering its membership. By the late 1960s, NOW had made significant political and legislative victories and was gaining enough power to become a major lobbying force. In 1969, newly elected representative

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita Chisholm ( ; ; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress. Chisholm represented New York's 12th congressional distr ...

of

New York gave her famous speech "Equal Rights for Women" on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressional passage

In February 1970, NOW picketed the United States Senate, a subcommittee of which was holding hearings on a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to 18. NOW disrupted the hearings and demanded a hearing on the Equal Rights Amendment and won a meeting with senators to discuss the ERA. That August, over 20,000 American women held a nationwide

Women's Strike for Equality

The Women's Strike for Equality was a strike which took place in the United States on August 26, 1970. It celebrated the 50th anniversary of the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, which effectively gave American women the right to vote.Gour ...

protest to demand full social, economic, and political equality.

[Nation, Women on](_blank)

''Time'' (New York), September 7, 1970 Said

Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan ( February 4, 1921 – February 4, 2006) was an American feminist writer and activist. A leading figure in the women's movement in the United States, her 1963 book ''The Feminine Mystique'' is often credited with sparking the se ...

of the strike, "All kinds of women's groups all over the country will be using this week on August 26 particularly, to point out those areas in women's life which are still not addressed. For example, a question of equality before the law; we are interested in the Equal Rights Amendment." Despite being centered in New York City—which was regarded as one of the biggest strongholds for NOW and other groups sympathetic to the

women's liberation movement

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism that emerged in the late 1960s and continued into the 1980s primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which effected great ...

such as

Redstockings

Redstockings, also known as Redstockings of the Women's Liberation Movement, is a radical feminist nonprofit that was founded in January 1969 in New York City, whose goal is "To Defend and Advance the Women's Liberation Agenda". The group's name ...

—and having a small number of participants in contrast to the large-scale anti-war and civil rights protests that had occurred in the recent time prior to the event,

the strike was credited as one of the biggest turning points in the rise of

second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades. It took place throughout the Western world, and aimed to increase equality for women by building on previous feminist gains.

Wh ...

.

In Washington, D.C., protesters presented a sympathetic Senate leadership with a petition for the Equal Rights Amendment at the

U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill at ...

. Influential news sources such as ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' also supported the cause of the protestors.

Soon after the strike took place, activists distributed literature across the country as well.

In 1970, congressional hearings began on the ERA.

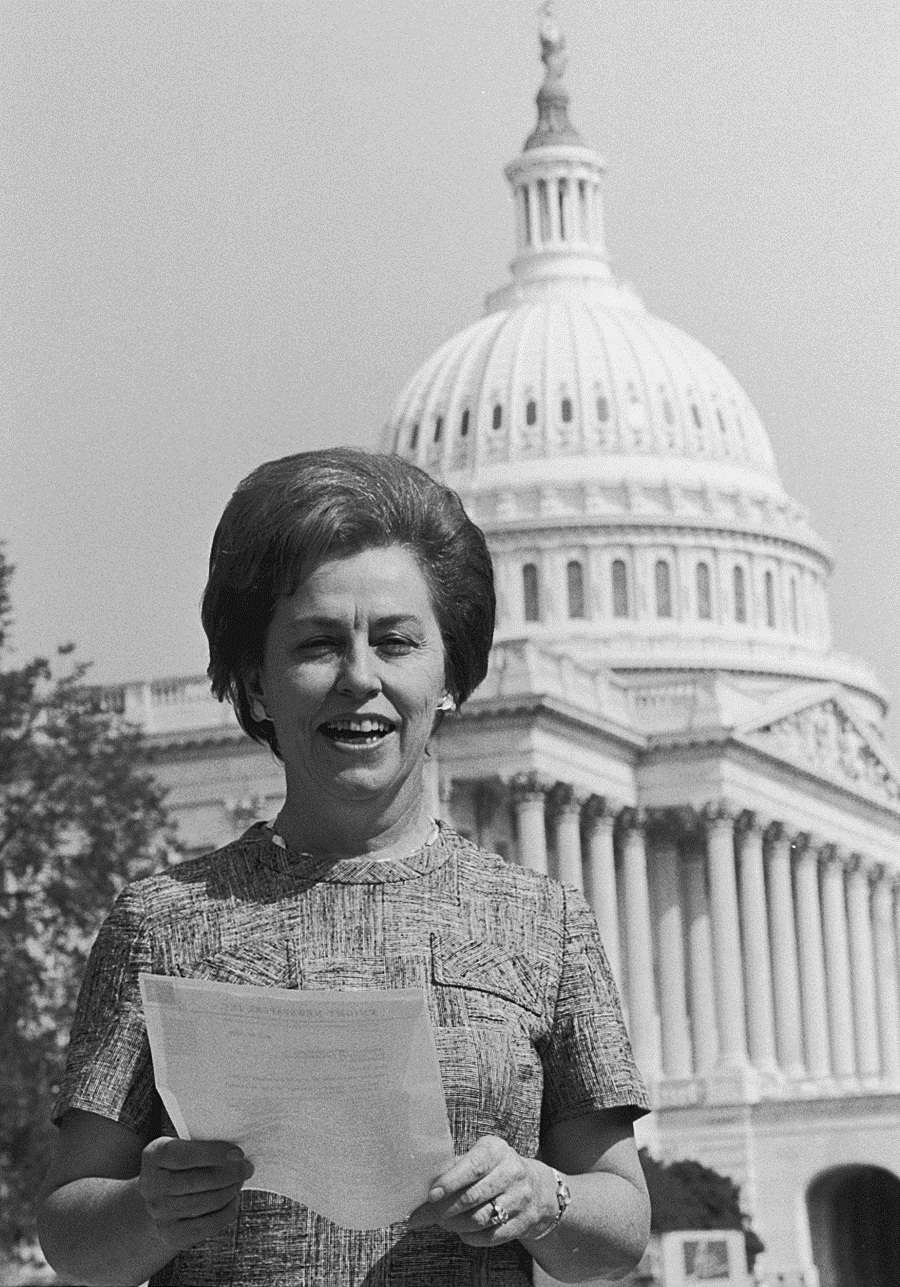

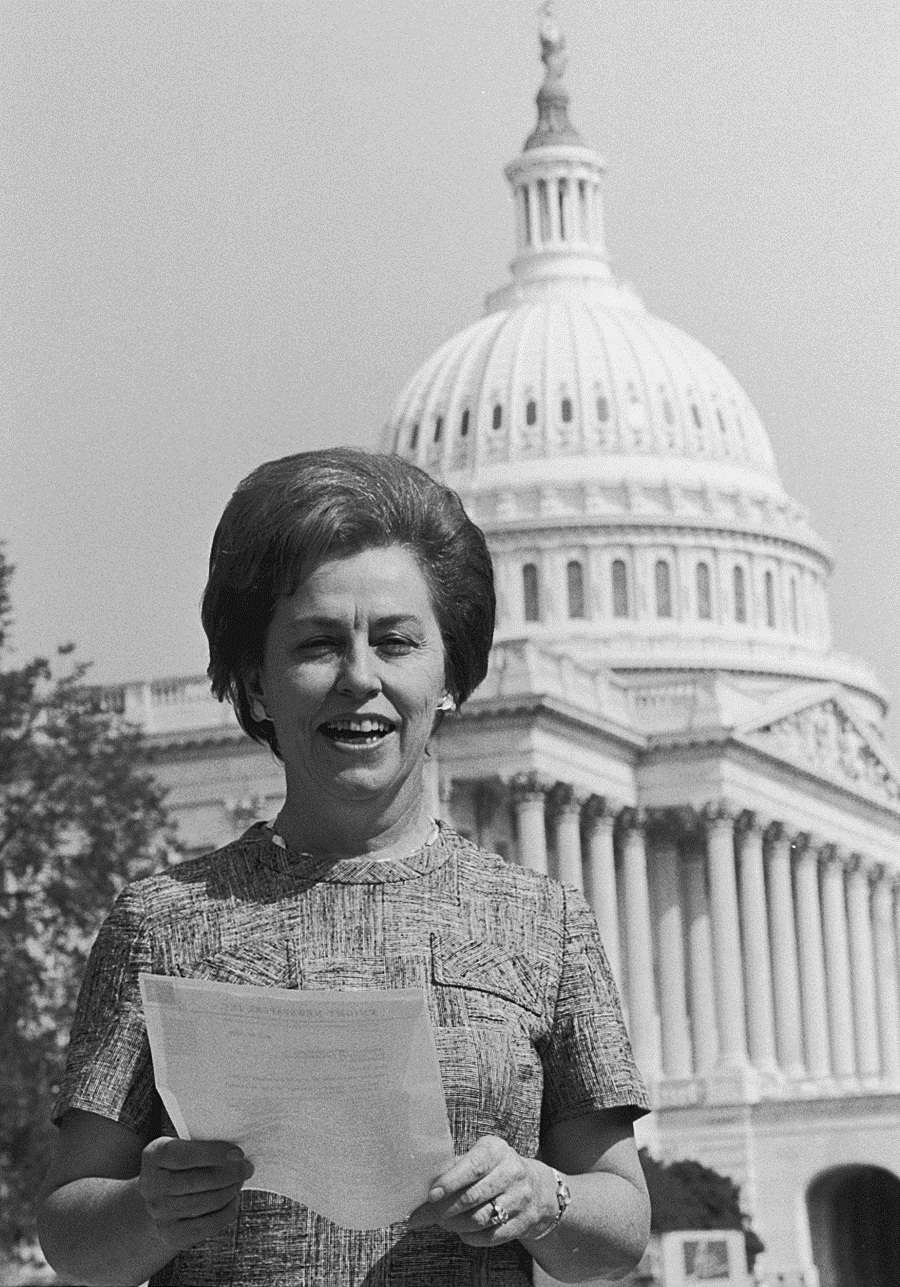

On August 10, 1970, Michigan Democrat

Martha Griffiths

Martha Wright Griffiths (January 29, 1912 – April 22, 2003) was an American lawyer and judge before being elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1954. Griffiths was the first woman to serve on the House Committee on Ways and M ...

successfully brought the Equal Rights Amendment to the House floor, after 15 years of the joint resolution having languished in the House Judiciary Committee. The joint resolution passed in the House and continued on to the Senate, which voted for the ERA with an added clause that women would be exempt from the military. The

91st Congress

The 91st United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1969, ...

, however, ended before the joint resolution could progress any further.

Griffiths reintroduced the ERA, and achieved success on Capitol Hill with her , which was adopted by the House on October 12, 1971, with a vote of 354 yeas (For), 24 nays (Against) and 51 not voting. Griffiths's joint resolution was then adopted by the Senate—without change—on March 22, 1972, by a vote of 84 yeas, 8 nays and 7 not voting. The Senate version, drafted by Senator

Birch Bayh

Birch Evans Bayh Jr. (; January 22, 1928 – March 14, 2019) was an American Democratic Party politician who served as U.S. Senator from Indiana from 1963 to 1981. He was first elected to office in 1954, when he won election to the India ...

of Indiana, passed after the defeat of an amendment proposed by Senator

Sam Ervin

Samuel James Ervin Jr. (September 27, 1896April 23, 1985) was an American politician. A Democrat, he served as a U.S. Senator from North Carolina from 1954 to 1974. A native of Morganton, he liked to call himself a "country lawyer", and often ...

of North Carolina that would have exempted women from the

draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

.

President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

immediately endorsed the ERA's approval upon its passage by the

92nd Congress

The 92nd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1971, ...

.

Actions in the state legislatures

Ratifications

On March 22, 1972, the ERA was placed before the state legislatures, with a seven-year deadline to acquire ratification by three-fourths (38) of the state legislatures. A majority of states ratified the proposed constitutional amendment within a year. Hawaii became the first state to ratify the ERA, which it did on the same day the amendment was approved by Congress: The U.S. Senate's vote on took place in the mid-to-late afternoon in Washington, D.C., when it was still midday in Hawaii. The

Hawaii Senate

The Hawaii Senate is the upper house of the Hawaii State Legislature. It consists of twenty-five members elected from an equal number of constituent districts across the islands and is led by the President of the Senate, elected from the membe ...

and

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

voted their approval shortly after noon Hawaii Standard Time.

During 1972, a total of 22 state legislatures ratified the amendment and eight more joined in early 1973. Between 1974 and 1977, only five states approved the ERA, and advocates became worried about the approaching March 22, 1979, deadline.

At the same time, the legislatures of five states that had ratified the ERA then adopted legislation purporting to rescind those ratifications. If, indeed, a state legislature has the ability to rescind, then the ERA actually had ratifications by only 30 states—not 35—when March 22, 1979, arrived.

The ERA has been ratified by the following states:

= Ratification revoked (see below)

** = Ratification revoked after June 30, 1982

#

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

(March 22, 1972)

#

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

(March 23, 1972)

#

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

(March 23, 1972)

#

Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

(March 24, 1972)

#

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

(March 24, 1972) *

#

Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

(March 28, 1972)

#

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

(March 29, 1972) *

#

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

(March 30, 1972)

#

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

(April 4, 1972) *

#

Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

(April 5, 1972)

#

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

(April 14, 1972)

#

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

(April 17, 1972)

#

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

(April 21, 1972)

#

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

(April 22, 1972)

#

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

(April 26, 1972)

#

New York (May 18, 1972)

#

Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

(May 22, 1972)

#

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

(May 26, 1972)

#

(June 21, 1972)

#

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

(June 27, 1972) *

#

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

(September 27, 1972)

#

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

(November 13, 1972)

#

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

(January 26, 1973)

#

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

(February 5, 1973) *

#

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

(February 8, 1973)

#

Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

(February 8, 1973)

#

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

(February 28, 1973)

#

Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

(March 1, 1973)

#

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

(March 15, 1973)

#

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

(March 22, 1973)

#

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

(January 18, 1974)

#

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

(January 25, 1974)

#

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

(February 7, 1974)

#

North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

(February 3, 1975)

**

#

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

(January 18, 1977)

#

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

(March 22, 2017)

#

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

(May 30, 2018)

#

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

(January 27, 2020)

Ratifications revoked

Although Article V is silent as to whether a state may

rescind

In contract law, rescission is an Equity (law), equitable legal remedy, remedy which allows a contractual party to cancel the contract. Parties may rescind if they are the victims of a vitiating factor, such as misrepresentation, Mistake (contrac ...

, or otherwise revoke, a previous ratification of a proposed—but not yet adopted—amendment to the U.S. Constitution, legislators in the following six states nevertheless voted to retract their earlier ratification of the ERA:

# Nebraska (March 15, 1973: Legislative Resolution No. 9)

# Tennessee (April 23, 1974: Senate Joint Resolution No. 29)

# Idaho (February 8, 1977: House Concurrent Resolution No. 10)

# Kentucky (March 17, 1978: House

ointResolution No. 20)

# South Dakota (March 5, 1979: Senate Joint Resolution No. 2)

# North Dakota (March 19, 2021: Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 4010)

The

lieutenant governor of Kentucky

The lieutenant governor of Kentucky was created under the state's second constitution, which was ratified in 1799. The inaugural officeholder was Alexander Scott Bullitt, who took office in 1800 following his election to serve under James Garrard ...

,

Thelma Stovall

Thelma Loyace Stovall (nee Hawkins; April 1, 1919 – February 4, 1994) was a pioneering American politician in the state of Kentucky. In 1949 she won election as state representative for Louisville, and served three consecutive terms. Over the n ...

, who was acting as governor in the governor's absence,

vetoed

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto pow ...

the rescinding resolution. Given that Article V explicitly provides that amendments are valid "when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states" this raised questions as to whether a state's governor, or someone temporarily acting as governor, has the power to veto any measure related to amending the United States Constitution.

On February 11, 2022, the West Virginia Senate passed a resolution rescinding West Virginia's ratification of the ERA but this resolution has not yet been adopted by the West Virginia House.

Sunsetting ratifications

South Dakota (pre-1979 deadline)

Among those rejecting Congress's claim to even hold authority to extend a previously established ratification deadline, the

South Dakota Legislature

The South Dakota State Legislature is the legislative branch of the government of South Dakota. It is a bicameral legislative body, consisting of the South Dakota Senate, which has 35 members, and the South Dakota House of Representatives, whic ...

adopted Senate Joint Resolution No. 2 on March 1, 1979. The joint resolution stipulated that South Dakota's 1973 ERA ratification would be

"sunsetted" as of the original deadline, March 22, 1979. South Dakota's 1979 sunset joint resolution declared: "the Ninety-fifth Congress ex post facto has sought unilaterally to alter the terms and conditions in such a way as to materially affect the congressionally established time period for ratification" (designated as "POM-93" by the U.S. Senate and published verbatim in the

Congressional Record of March 13, 1979, at pages 4861 and 4862).

The action on the part of South Dakota lawmakers—occurring 21 days prior to originally agreed-upon deadline of March 22, 1979—could be viewed as slightly different from a rescission.

''Constitution Annotated'' notes that "

ur states had rescinded their ratifications

f the ERAand a fifth had declared that its ratification would be void unless the amendment was ratified within the original time limit", with a footnote identifying South Dakota as that "fifth" state.

North Dakota (post-1979 deadline)

On March 19, 2021,

North Dakota state lawmakers adopted Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 4010 to retroactively clarify that North Dakota's 1975 ratification of the ERA was valid only through "...11:59 p.m. on March 22, 1979..." and went on to proclaim that North Dakota "...should not be counted by Congress, the Archivist of the United States, lawmakers in any other state, any court of law, or any other person, as still having on record a live ratification of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution of the United States as was offered by House Joint Resolution No. 208 of the 92nd Congress on March 22, 1972...." The resolution was formally received by the U.S. Senate on April 20, 2021, was designated as "POM-10", was referred to the Senate's Judiciary Committee, and its full and complete verbatim text was published at page S2066 of the ''Congressional Record''.

Minnesota (2021 proposal)

A resolution was introduced in the

Minnesota Senate

The Minnesota Senate is the upper house of the Legislature of the U.S. state of Minnesota. At 67 members, half as many as the Minnesota House of Representatives, it is the largest upper house of any U.S. state legislature. Floor sessions are h ...

on January 11, 2021, which—if adopted—would retroactively clarify that Minnesota's 1973 ratification of the ERA expired as of the originally-designated March 22, 1979, deadline.

Non-ratifying states with one-house approval

At various times, in six of the 12 non-ratifying states, one house of the legislature approved the ERA. It failed in those states because both houses of a state's legislature must approve, during the same session, in order for that state to be deemed to have ratified.

#

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

: State House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on March 22, 1972, with a tally of 83 to zero.

#

Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

: State Senate voted to ratify the ERA on March 23, 1972, by a

voice vote

In parliamentary procedure, a voice vote (from the Latin ''viva voce'', meaning "live voice") or acclamation is a voting method in deliberative assemblies (such as legislatures) in which a group vote is taken on a topic or motion by responding vo ...

.

#

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

: State House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on March 24, 1972, with a tally of 91 to 4; a second time on April 10, 1975, with a tally of 62 to 58; a third time on May 17, 1979, with a tally of 66 to 53; and a fourth time on June 21, 1982, with a tally of 60 to 58.

#

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

: State Senate voted to ratify the ERA on June 7, 1972, with a tally of 25 to 13.

#

Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

: State House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on February 7, 1975, with a tally of 82 to 75.

#

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

: State House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on February 9, 1977, with a tally of 61 to 55.

Ratification resolutions have also been defeated in Arizona, Arkansas, and Mississippi.

Congressional extension of ratification deadline

The original joint resolution (), by which the

92nd Congress

The 92nd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1971, ...

proposed the amendment to the states, was prefaced by the following resolving clause:

As the joint resolution was passed on March 22, 1972, this effectively set March 22, 1979 as the deadline for the amendment to be ratified by the requisite number of states. However, the 92nd Congress did not incorporate any time limit into the body of the actual text of the proposed amendment, as had been done with a number of other proposed amendments.

In 1978, as the original 1979 deadline approached, the

95th Congress

The 95th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1977, ...

adopted , by Representative

Elizabeth Holtzman

Elizabeth Holtzman (born August 11, 1941) is an American attorney and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives from New York's 16th congressional district as a member of the Democratic Party from 1973 to 1981. She the ...

of

New York (House: August; Senate: October 6; signing of the President: October 20), which purported to extend the ERA's ratification deadline to June 30, 1982. H.J.Res. 638 received less than two-thirds of the vote (a

simple majority, not a

supermajority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority ru ...

) in both the House of Representatives and the Senate; for that reason, ERA supporters deemed it necessary that H.J.Res. 638 be transmitted to then-President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

for signature as a safety precaution. The

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled in ''

Hollingsworth v. Virginia

''Hollingsworth v. Virginia'', 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 378 (1798), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court ruled early in America's history that the President of the United States has no formal role in the p ...

'' (1798)

that the

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

has no formal role in the passing of constitutional amendments. Carter signed the joint resolution, although he noted, on strictly procedural grounds, the irregularity of his doing so given the Supreme Court's decision in 1798. During this disputed extension of slightly more than three years, no additional states ratified or

rescinded.

The purported extension of ERA's ratification deadline was vigorously contested in 1978 as scholars were divided as to whether Congress actually has authority to revise a previously agreed-to deadline for the states to act upon a constitutional amendment. On June 18, 1980, a resolution in the Illinois House of Representatives resulted in a vote of 102–71 in favor, but Illinois' internal parliamentary rules required a three-fifths majority on constitutional amendments and so the measure failed by five votes. In 1982, seven female ERA supporters, known as the

Grassroots Group of Second Class Citizens, went on a fast and seventeen chained themselves to the entrance of the Illinois Senate chamber.

The closest that the ERA came to gaining an additional ratification between the original deadline of March 22, 1979, and the revised June 30, 1982, expiration date was when it was approved by the

Florida House of Representatives

The Florida House of Representatives is the lower house of the Florida Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Florida, the Florida Senate being the upper house. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution of Florida, adopted ...

on June 21, 1982. In the final week before the revised deadline, that ratifying resolution, however, was defeated in the

Florida Senate

The Florida Senate is the upper house of the Florida Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Florida, the Florida House of Representatives being the lower house. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution of Florida, adopted ...

by a vote of 16 to 22. Even if Florida had ratified the ERA, the proposed amendment would still have fallen short of the required 38. Many ERA supporters mourned the failure of the amendment. For example, a

jazz funeral for the ERA was held in New Orleans in July 1982.

According to research by Jules B. Gerard, professor of law at

Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University is r ...

, of the 35 legislatures that passed ratification resolutions, 24 of them explicitly referred to the original 1979 deadline.

Lawsuit regarding deadline extension

On December 23, 1981, a federal district court, in the case of ''Idaho v. Freeman'', ruled that the extension of the ERA ratification deadline to June 30, 1982 was not valid, and that ERA had actually expired from state legislative consideration more than two years earlier on the original expiration date of March 22, 1979. On January 25, 1982, however, the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

stayed the lower court's decision.

After the disputed June 30, 1982, extended deadline had come and gone, the Supreme Court, at the beginning of its new term, on October 4, 1982, in the separate case of ''NOW v. Idaho'', 459 U.S. 809 (1982), vacated the federal district court decision in ''Idaho v. Freeman'', which, in addition to declaring March 22, 1979, as ERA's expiration date, had upheld the validity of state rescissions. The Supreme Court declared these controversies

moot

Moot may refer to:

* Mootness, in American law: a point where further proceedings have lost practical significance; whereas in British law: the issue remains debatable

* Moot court, an activity in many law schools where participants take part in s ...

based on the

memorandum

A memorandum ( : memoranda; abbr: memo; from the Latin ''memorandum'', "(that) which is to be remembered") is a written message that is typically used in a professional setting. Commonly abbreviated "memo," these messages are usually brief and ...

of the appellant Gerald P. Carmen, the then-

Administrator of General Services

The General Services Administration (GSA) is an independent agency of the United States government established in 1949 to help manage and support the basic functioning of federal agencies. GSA supplies products and communications for U.S. gove ...

, that the ERA had not received the required number of ratifications (38) and so "the Amendment has failed of adoption no matter what the resolution of the legal issues presented here."

In the 1939 case of ''

Coleman v. Miller

''Coleman v. Miller'', 307 U.S. 433 (1939), is a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court which clarified that if the Congress of the United States—when proposing for ratification an amendment to the United States Constitution, ...

'', the Supreme Court ruled that Congress has the final authority to determine whether, by lapse of time, a proposed constitutional amendment has lost its vitality before being ratified by enough states, and whether state ratifications are effective in light of attempts at subsequent withdrawal. The Court stated: "We think that, in accordance with this historic precedent, the question of the efficacy of ratifications by state legislatures, in the light of previous rejection or attempted withdrawal, should be regarded as a political question pertaining to the political departments, with the ultimate authority in the Congress in the exercise of its control over the promulgation of the adoption of the amendment."

In the context of this judicial precedent, nonpartisan counsel to a Nevada state legislative committee concluded in 2017 that "If three more states sent their ratification to the appropriate federal official, it would then be up to Congress to determine whether a sufficient number of states have ratified the Equal Rights Amendment." In 2018, Virginia attorney general

Mark Herring

Mark Rankin Herring (born September 25, 1961) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 47th Attorney General of Virginia from 2014 to 2022. A Democrat, he previously served in the Senate of Virginia since a 2006 special election, ...

wrote an opinion suggesting that Congress could extend or remove the ratification deadline.

Lawsuits regarding ratification

Alabama lawsuit to opposing ratification

On December 16, 2019, the states of Alabama, Louisiana and South Dakota sued to prevent further ratifying of the Equal Rights Amendment. Alabama Attorney General

Steve Marshall stated, "The people had seven years to consider the ERA, and they rejected it. To sneak it into the Constitution through this illegal process would undermine the very basis for our constitutional order."

South Dakota Attorney General

Jason Ravnsborg

Jason Richard Ravnsborg (born April 12, 1976) is an American attorney and politician. A Republican, he served as Attorney General of South Dakota from 2019 until his removal in 2022. Ravnsborg ran for the U.S. Senate in 2014, losing in the Repub ...

stated in a press release:

On January 6, 2020, the Department of Justice

Office of Legal Counsel

The Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) is an office in the United States Department of Justice that assists the Attorney General's position as legal adviser to the President and all executive branch agencies. It drafts legal opinions of the Attorney ...

official Steven Engel issued an opinion in response to the lawsuit by Alabama, Louisiana, and South Dakota, stating that "We conclude that Congress had the constitutional authority to impose a deadline on the ratification of the ERA and, because that deadline has expired, the ERA Resolution is no longer pending before the States." The OLC argued in part that Congress had the authority to impose a deadline for the ERA and that it did not have the authority to retroactively extend the deadline once it had expired.

On February 27, 2020, the States of Alabama, Louisiana and South Dakota entered into a joint stipulation and voluntary dismissal with the Archivist of the United States. The joint stipulation incorporated the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel's opinion; stated that the Archivist would not certify the adoption of the Equal Rights Amendment and stated that if the Department of Justice ever concludes that the 1972 ERA Resolution is still pending and that the Archivist therefore has authority to certify the ERA's adoption ... the Archivist will make no certification concerning ratification of the ERA until at least 45 days following the announcement of the Department of Justice's conclusion, absent a court order compelling him to do so sooner." On March 2, 2020, Federal District Court Judge

L. Scott Coogler entered an order regarding the Joint Stipulation and Plaintiff's Voluntary Dismissal, granting the dismissal without prejudice.

Massachusetts lawsuit supporting ratification

On January 7, 2020, a complaint was filed by Equal Means Equal, The Yellow Roses and Katherine Weitbrecht in the

against the Archivist of the United States seeking to have him count the three most recently ratifying states and certify the ERA as having become part of the United States Constitution. On August 6, 2020, Judge

Denise Casper granted the Archivist's motion to dismiss, ruling that the plaintiffs did not have

standing

Standing, also referred to as orthostasis, is a position in which the body is held in an ''erect'' ("orthostatic") position and supported only by the feet. Although seemingly static, the body rocks slightly back and forth from the ankle in the s ...

to sue to compel the Archivist to certify and so she could not rule on the merits of the case. On August 21, 2020, the plaintiffs appealed this decision to the

United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (in case citations, 1st Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* District of Maine

* District of Massachusetts

* ...

and on September 2, 2020, the plaintiffs asked the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

to hear this case. Subsequently, the Supreme Court denied the request to intervene before the First Circuit gives its decision. On June 29, 2021, the First Circuit affirmed the District Court's decision that "the plaintiffs have not met their burden at the pleading stage with respect to those federal constitutional requirements, we affirm the order dismissing their suit for lack of standing." An ''en banc'' rehearing request was denied on January 4, 2022.

2020 U.S. District Court lawsuit supporting ratification

On January 30, 2020, the attorneys general of Virginia, Illinois and Nevada filed a lawsuit to require the

Archivist of the United States to "carry out his statutory duty of recognizing the complete and final adoption" of the ERA as the Twenty-eighth Amendment to the Constitution.

On February 19, 2020, the States of Alabama, Louisiana, Nebraska, South Dakota and Tennessee moved to intervene in the case. On March 10, 2020, the Plaintiff States (Virginia, Illinois and Nevada) filed a memorandum in opposition to the five states seeking to intervene. On May 7, 2020, the DOJ filed a motion to dismiss, claiming the states do not have

standing

Standing, also referred to as orthostasis, is a position in which the body is held in an ''erect'' ("orthostatic") position and supported only by the feet. Although seemingly static, the body rocks slightly back and forth from the ankle in the s ...

to bring the case to trial as they have to show any "concrete injury", nor that the case was

ripe

Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE, French for "European IP Networks") is a forum open to all parties with an interest in the technical development of the Internet. The RIPE community's objective is to ensure that the administrative and technical coor ...

for review.

On June 12, 2020, the District Court granted the Intervening states (Alabama, Louisiana, Nebraska, South Dakota and Tennessee) motion to intervene in the case. On March 5, 2021, federal judge

Rudolph Contreras

Rudolph Contreras (born December 6, 1962) is a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. He also serves as Presiding Judge on the United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

In De ...

of the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

The United States District Court for the District of Columbia (in case citations, D.D.C.) is a federal district court in the District of Columbia. It also occasionally handles (jointly with the United States District Court for the District of ...

ruled that the ratification period for the ERA "expired long ago" and that three states' recent ratifications had come too late to be counted in the amendment's favor. On May 3, 2021, the plaintiff states appealed the ruling to the

. Virginia withdrew from the lawsuit in February 2022. Oral arguments were held on September 28, 2022, before a panel composed by judges

Wilkins,

Rao and

Childs.

Support for the ERA

Supporters of the ERA point to the lack of a specific guarantee in the Constitution for equal rights protections on the basis of sex. In 1973, future Supreme Court justice

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by President ...

summarized a supporting argument for the ERA in the ''

American Bar Association Journal

The ''ABA Journal'' (since 1984, formerly ''American Bar Association Journal'', 1915–1983, evolved from '' Annual Bulletin'', 1908–1914) is a monthly legal trade magazine and the flagship publication of the American Bar Association. It is no ...

'':

The equal rights amendment, in sum, would dedicate the nation to a new view of the rights and responsibilities of men and women. It firmly rejects sharp legislative lines between the sexes as constitutionally tolerable. Instead, it looks toward a legal system in which each person will be judged on the basis of individual merit and not on the basis of an unalterable trait of birth that bears no necessary relationship to need or ability.

Later, Ginsburg voiced her opinion that the best course of action on the Equal Rights Amendment is to start over, due to being past its expiration date. While at a discussion at Georgetown University in February 2020, Ginsburg noted the challenge that "if you count a latecomer on the plus side, how can you disregard states that said 'we've changed our minds?'"

In the early 1940s, both the Democratic and Republican parties added support for the ERA to their platforms.

The

National Organization for Women

The National Organization for Women (NOW) is an American feminist organization. Founded in 1966, it is legally a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. The organization consists of 550 chapters in all 50 U.S. states and in Washington, D.C. It ...

(NOW) and

ERAmerica, a coalition of almost 80 organizations, led the pro-ERA efforts. Between 1972 and 1982, ERA supporters held rallies, petitioned, picketed, went on hunger strikes, and performed acts of civil disobedience.

On July 9, 1978, NOW and other organizations hosted a national march in Washington, D.C., which garnered over 100,000 supporters, and was followed by a Lobby Day on July 10. On June 6, 1982, NOW sponsored marches in states that had not passed the ERA including Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, and Oklahoma. Key feminists of the time, such as

Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism